The 11th European Forum on the Rights of the Child took place in Brussels on 7-8 November 2017, entitled “Children deprived of liberty and alternatives to detention,” bringing together over 350 participants from UN agencies and bodies, global, European and national organisations and individuals working to protect, defend and promote the implementation of the rights of children deprived of liberty and those with parents in prison. The event, which focused on raising awareness, facilitating implementation and promoting the use/expansion of alternative measures to custody while clarifying standards relevant to them, was held within the context of the forthcoming UN Global study on children deprived of liberty, and in follow-up to the 12 April 2017 Communication on the protection of children in migration.

High level plenary sessions over the two-day event looked at EU and international commitments on children deprived of liberty, highlighting challenges and latest developments. During the Day One plenary session, Manfred Nowak, Independent Expert for the United Nations Secretary-General’s Study on children deprived of liberty and Professor of international law and human rights at the University of Vienna, presented the UN Global Study on Children Deprived of Liberty, which provided an overarching framework for the EU Forum.

“Appeals to governments to make contributions to the Study were heard, to shine a much-needed spotlight on children in detention, whether in alternative care/institutions, immigration detention or living with their parents in prison”

The core objectives of the UN Global Study on Children Deprived of Liberty are to: assess the magnitude of this phenomenon, including the number of children deprived of liberty (broken down by age, gender, ethnic, social and national origin, disability and other grounds), as well as the reasons invoked, the root-causes, type and length of deprivation of liberty and places of detention; document good practices and capture the views and experiences of children to inform the Global Study’s recommendations; promote a change in stigmatising attitudes and behaviour towards children at risk or who are deprived of liberty; and provide recommendations for law, policy and practice to safeguard the rights of children concerned, and prevent and significantly reduce the number of children deprived of liberty through effective non-custodial alternatives, guided by the best interests of the child.

Appeals to governments worldwide to make specific contributions to enable the completion of the UN Global Study were heard throughout the event, to shine a much-needed spotlight on children in detention, whether in alternative care/institutions, immigration detention or living with their parents in prison. To date, only two countries — Austria and Switzerland — have contributed funding to the €4.7 million needed to carry out the study.

“Why are prisoners and their families always last on the agenda?”

On Day Two, keynote speaker Judge Renate Winter, Chair of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, raised the issue of how to highlight the “added value” of an initiative as she inveighed against this inertia, questioning Member State inaction in funding the Global Study. Were they afraid of the truth? Is detention easier (the problem remains out of sight)? Where is the added value of this study and how do we “sell” it? What is of value, if not human rights? As a concluding comment, she also emphasised the need for children separated from a parent in prison to be higher up on agendas in general.

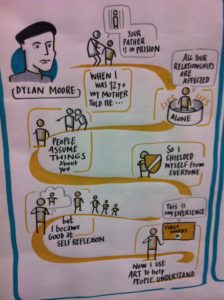

Indeed, COPE is grateful to Child Rights Coordinator Margaret Tuite and her team for putting children separated from a parent in prison on the agenda as part of the Forum’s overarching theme. Personal testimonies by young people affected by parental detention brought the specific issues and needs front and centre during the three-day event. Dylan Moore from Scotland spoke about his experience after his father was imprisoned, the isolation and stigma it brought, the need to mask the issue from his friends, build a wall around himself, and provide support for his mother:

When my mum told me that my dad was in prison, I was 12 years old and just about to start high school. I think that people can assume parental imprisonment only affects the child’s relationship with that parent, but it can have an effect on almost every other aspect of their life. As a child, I felt completely disconnected from everyone.

. . . I could see my mother’s pain when she told me the truth about him, and knew that she’d obviously gone through a lot which she’d hidden from me. My parents were not together, and so I felt a responsibility not to talk to her about my dad in order to spare her any more pain. At 12 years old, we’re usually just beginning to develop a sense of our own identity — but having a parent in prison essentially launches you into adulthood whether you’re ready or not. You’re dealing with a very adult situation. In some ways the parent/child roles are switched — I assumed all the control in the relationship with my father, because I had all the responsibility of maintaining it.

“I felt like I just didn’t really belong anywhere… When you’re carrying around this huge burden it makes it almost impossible to truly establish an emotional connection with anyone… I felt like the only person in the world with this experience”

School becomes something of a mine trap — gossip and rumours spread fast, and so the last thing you want is for someone to find out, and there’s so much stigma attached to parental imprisonment — people assume things about your living environment, how you were raised, and even the other parent. It forces you to become a really good liar. I had to be prepared with a lie in any conversation I had, in case someone asked about my dad. When you’re so concerned with not slipping up all the time, and you’re carrying around this huge burden it makes it almost impossible to truly establish an emotional connection with anyone.

So I ended up in this situation where I felt like I just didn’t really belong anywhere — the fact that my dad was in prison was a huge part of my life and my history and I couldn’t share that or express my feelings about it. So I retreated into myself, I spent a lot of time alone, had very poor social skills and was generally very unhappy for a number of years.

In hindsight the only reason I felt like I had to hide it is because I’d never heard anyone talk about it before. We had never discussed the legal system in school. There was no information on how to deal with this at all, and I truly felt like I was the only person in the world with this experience.

Dylan later started working with KIN, an arts collective for young people who’d experienced familial imprisonment, and began to channel his energies and emotions using art, poetry, other means of expression. He and a group of other young people created First Words, a video conveying their reflections and feelings, how they have navigated the issue and found ways other than their experience with prison to define themselves.

Personal testimony by another person affected by a father’s imprisonment was also heard on Day Two, this time from Sweden. During a parallel session on children with imprisoned parents, co-chaired by Chiara Adamo, Head of Unit, Fundamental Rights Policy, Directorate-General Justice and Consumers and Nancy Loucks, Chief Executive, Families Outside; Secretary General, COPE, Linnéa spoke about her experience having a father in prison when she was growing up, recalling how happy she was when her father was able to return to the family home through the use of electronic monitoring.

The session, featuring presentations from Hungary, Italy, Croatia, Romania, Sweden and Slovenia, focused on measures that help maintain family contact, such as the use of probation. Iuliana Carbanaru, Probation Inspector at the Romanian Ministry of Justice’s National Probation Directorate, highlighted how the use of probation has reduced prison sentences.

She described an initiative revolving around interviews with parents on probation that explored how their children experienced their parents’ conviction and enforcement of probation sanctions. Children’s positive reactions to probation sentences included: “because we can stay together”, “the family will be together”, ”our family will not be affected”, “a mistake had been made and this is the payment”.

Bea Francija Nad, Head of Service of General Treatment, the Croatian Prison Service, presented child-friendly initiatives within her context, working closely with the NGO RODA and emphasising how family contact between children of prisoners and incarcerated mothers increased dramatically during the two-year EU funded MA#ME project. Croatia has only one prison establishment for women, and children and families often have to travel great distances to visit with their mothers in prison.

Likewise, Lucija Bozikova, Head of Treatment Division, Prison Administration, Ministry of Justice, Slovenia, highlighted how family contact initiatives for children with parents in prison in her country were enhanced following a COPE exploratory mission there in 2013, funded as part of an EU Operating Grant for the European network. Liz Ayre, Executive Director of COPE, pointed out the crucial importance of EU funding in promoting initiatives across Europe — noting, for example, how children’s contact with imprisoned mothers in Croatia had declined dramatically since the end of the two-year EU-funded MA#ME project.

Also on the panel were Metella Romana Pasquini, Department of Penitentiary Administration, Italian Ministry of Justice, and Lia Sacerdote, Bambinisenzasbarre ONLUS. They highlighted the progress made working jointly since the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding on Children of Prisoners (MoU), comparing child-friendly prison initiatives and schemes in Italy in 2013, prior to the MoU’s signature in 2014, to those found three years on, in 2016 and noting the progress since. During the Forum, the Commission committed to promoting the Italian MoU.

“the importance of community-based initiatives, parent support programmes and alternatives to custody that permit greater contact for children and imprisoned parents”

Attila Juhasz, Prison Governor, Heves County Penitentiary Institute of Hungary, and Madelein Kattell of BUFFF Sweden highlighted the importance of community-based initiatives, parent support programmes and alternatives to custody that permit greater contact for children and imprisoned parents. Juhasz emphasised the important role of the media in supporting initiatives; media portrayals in some countries can undermine the effectiveness of support initiatives.

Prior to the official start of the Forum, a series of side events were planned, which offered ample opportunity to consider the many intersections among the topics covered by the Forum, such as the high proportion of children in institutions or care who end up in conflict with the law. One such side event was entitled “Vulnerabilities and pathways related to parental imprisonment.” Rachel Brett represented the COPE network on the panel, speaking about how the actual physical and emotional separation caused by a parent’s imprisonment has a more negative impact on the child than non-custodial alternatives. Some children live in prison with their parent; a 2017 report by the EU Fundamental Rights Agency covers the ages from and up to which a child can stay in prison with the parent, under criminal law.

Rachel also raised the question of children of prisoners who live in institutions, highlighting the paucity of data and information on the numbers of children this entails. Institutionalisation, she explained, may be directly due to parental incarceration, or indirectly (e.g., increased poverty leading to lack of adequate housing, ability of other parent/carers to provide for the child), related to underlying circumstances which also led to parent’s imprisonment (e.g., addiction, domestic violence), or unrelated. She questioned that, given that one of the key findings from the EU FP7 funded COPING research project was the benefits for the children of maintaining contact with and visiting their imprisoned parents—except in specific cases when not in their best interests—how are children in institutions/care enabled to do this?

“Rachel highlighted difficulties prisoners from ethnic minorities may face in being eligible for alternatives to imprisonment, which require a place of residence, a job and a foothold in the community”

Rachel also provided information on the specific situation of children of ethnic minorities, notably Roma and Travellers, whose parents are in prison. She posited reasons for their over-representation in prison populations, including being more often subjected to police stop and search operations; and highlighted difficulties they may face while in custody in being eligible for alternatives to imprisonment, including early release, which frequently require a place of residence, a job and a foothold in the community.

During the side event, Lina Hellmar, a youth worker with BUFFF Sweden who experienced the imprisonment of her mother while growing up, spoke about her feelings of loneliness and shame, building a wall between herself and others, remaining vigilant at all times, becoming “a chameleon” to blend in, yet experiencing a sense of relief when her mother was in prison as she at least knew she was “safe”. She explained how she has since salvaged her relationship with her mother, who is “more like a friend than a mother”, and how now, as a mother herself, she struggles with her own feelings at times. She expressed a longing to have had the kind of support growing up that is available to others now, from NGO BUFFF and other members of the COPE network across Europe.

COPE works closely with the European Union, a primary funder of the network since 2013, and, through the COPING and DIHR transnational research projects, a partner since 2009. COPE is currently participating with the PC-CP[1] in the elaboration of a draft Council of Europe Recommendation for Children with Imprisoned Parents, scheduled to go to the Committee of Ministers in January 2018. The Recommendation is accompanied by an Explanatory Report, and a COE questionnaire on child-friendly prison practices that has been sent to all Council of Europe member states. An estimated 2.1 million children are separated from a parent in prison in Council of Europe countries[2] at any given time each year (stock rate); 800,000 children in EU-28, which impacts on the rights of children in multiple ways.

[1] Council for Penological Co-operation

[2] Extrapolation based on a 1999 national census in France carried out by the French institute for statistics (INSEE) that included 1,700 male prisoners and established a ‘parenting rate’ of 1.3 per male prisoner.