This week, COPE’s Not My Crime, Still My Sentence campaign will be focusing on the theme of maintaining family ties through prison visits and alternative communications. The absence of a parent can significantly change the family dynamic and can have negative effects on a child’s development. COPE wants to raise awareness about the importance of fostering the bond between children and their imprisoned parents by highlighting some of the work that its members have carried out around this issue.

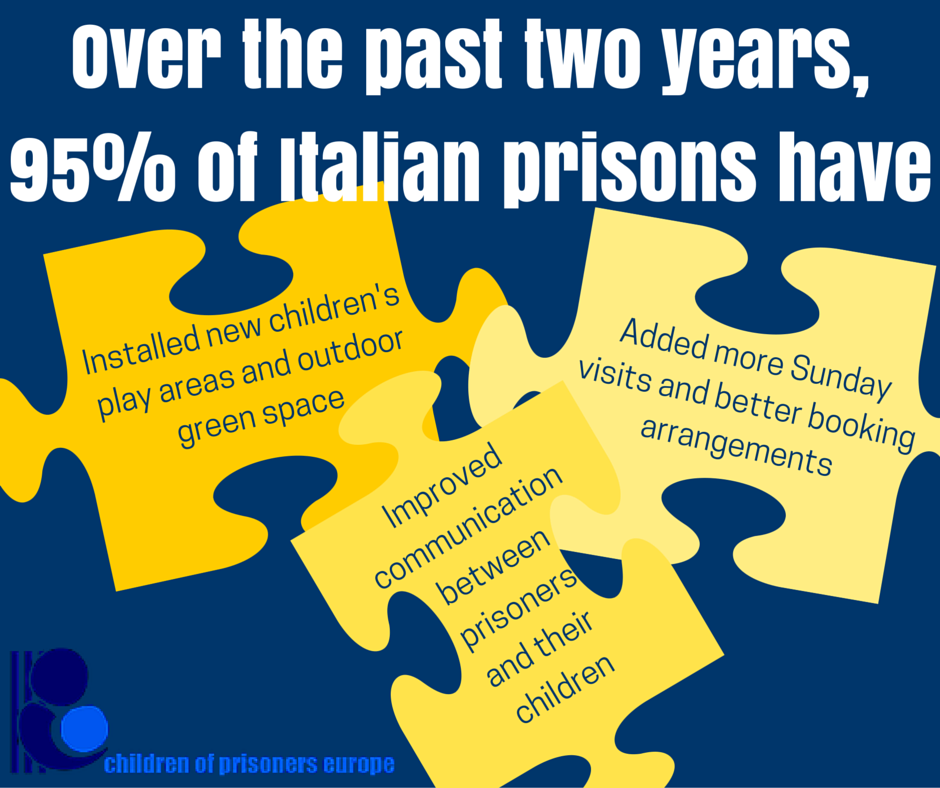

The Italian Memorandum of Understanding on children with imprisoned parents offers some helpful guidelines on how prisons can accommodate time and space for children and parents to foster their relationships. Article 2 of the Memorandum underscores the importance of placing parents in prisons that are geographically close to their children in order to facilitate visits. This article also asks that visiting times be available six days a week, at least two of which must be scheduled in the afternoon in order to allow children to visit without missing school. Sundays and holidays are also requested as visiting times because they are often important days for family bonding outside of the prison context and the continuation of that patterned bonding time is important for the child’s healthy development.

Articles 2 and 3 both mention how essential it is for children to be able to visit their imprisoned parent within a week of their imprisonment, instead of granting prisoners visiting rights only after they have demonstrated “good behaviour”. Having to wait a month or more is a very long time for children and can cause anxiety and separation trauma. Visiting a parent in prison is the child’s right and should not be used as a “reward” for the imprisoned parent’s behaviour.

In Northern Ireland, COPE affiliate Barnardo’s has made good progress in implementing visiting hours that are compatible with children’s school schedules. The Hydebank Wood Women’s Prison for instance, offers four “Family Ties” days per year that coincide with school holidays. Magilligan Prison offers parenting trainings and those who complete the training are given an extra visit day where they receive a certificate of achievement and share what they learned with their partners and children. Similarly, Maghaberry Prison offers a “Family Matters” programme that includes a “Big Visit” focused around child-parent bonding.

It is important that prison staff take the child’s perspective into account when it comes to imprisoned parents. Article 2 calls for “children’s expert groups” to be formed in each prison and to meet regularly to discuss how the prison is facilitating and promoting the child-parent bond. In Turkish prisons, for example, our affiliate Youth Re-Autonomy Foundation of Turkey (TCYOV) has worked to implement “women-centered support models”; a project that trained both imprisoned mothers and prison staff in understanding the psycho-social development of children. After the training, 60% of mothers said they understood how to maintain a healthy relationship with their children while in prison. The training has now been put into a booklet complete with data and qualitative observations, to be used as an advocacy tool for its implementation beyond just the five cities in which it was tested.

Furthermore, article 3 of the Memorandum states that the signatories agree to develop guidelines for maintaining the family bond when physical contact is not an option. The use of internet for video calls or messaging has been an important development in this regard. Even if regular physical contact is not feasible, prisons must provide alternative avenues for children to communicate with their imprisoned parent. In England and Wales, COPE’s partners have developed a project called “Storybook Dads”, a programme that allows imprisoned fathers to record themselves reading a story to their children. The children can then record their comments and reactions to the story for the fathers’ listening. This is a great way to foster family ties while also encouraging literacy, both of which are positive for a child’s growth and development.

While video calls and storybook recordings can be great resources for maintaining family ties, the physical separation between children and their parents can still be very difficult for children’s emotional and psycho-social development. It is important for prisons to not become overly reliant on non-physical forms of communication. These forms of communication should not replace real visits in which children can play with, hug and cuddle their parents. The child’s healthy development should be kept at the centre of all decisions and policies regarding an imprisoned parent’s opportunities to foster family ties.

More information on how COPE’s members have been working to maintain family ties between children and their imprisoned parents will be posted throughout the week on Facebook and Twitter. You do not need an account to view these pages.